Nostalgia, Ultra

When Kruder & Dorfmeister's downbeats ruled the world

According to the late Austrian journalist Sven Gächter, everyone owned at least two things in the 1990s.

A white Ikea Billy bookshelf and a Kruder & Dorfmeister CD.

There’s some truth to that bonmot. The Viennese duo’s ambient trip-hop was truly inescapable. You heard it in clubs and cafés, in boutiques and in your friends’ apartments, which were crammed with Billy bookshelves.

K&D’s defining work consisted of a mix CD and a remix compilation, both released on the !K7 label, selling over a million copies in total.

DJ-Kicks: Kruder & Dorfmeister, sold 425,000 units.

The K&D Sessions went on to sell 850,000.1

It’s unlikely that a DJ mix or a remix compilation will ever have such an impact again. In the streaming era, there’s nothing more disposable that last week’s Mixcloud set.

The story of K&D started in 1991, when hairdresser and hip-hop head Peter Kruder met studied flautist Richard Dorfmeister in Vienna’s underground music scene.

Hanging out in Kruder’s living room in the multicultural 16th district, they smoked copious amounts of weed while making beats together, at an unhurried pace often associated with the city’s lifestyle.

For a while, they left the apartment only for groceries.

Rummaging their friends’ record collections and the city’s second hand record stores, they created laid-back instrumental tracks with roots in hip-hop, acid jazz and dub.

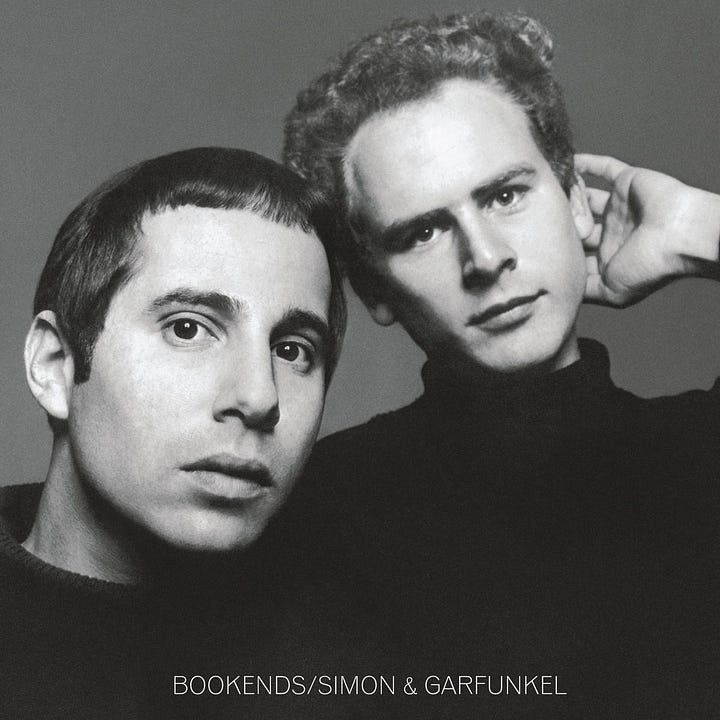

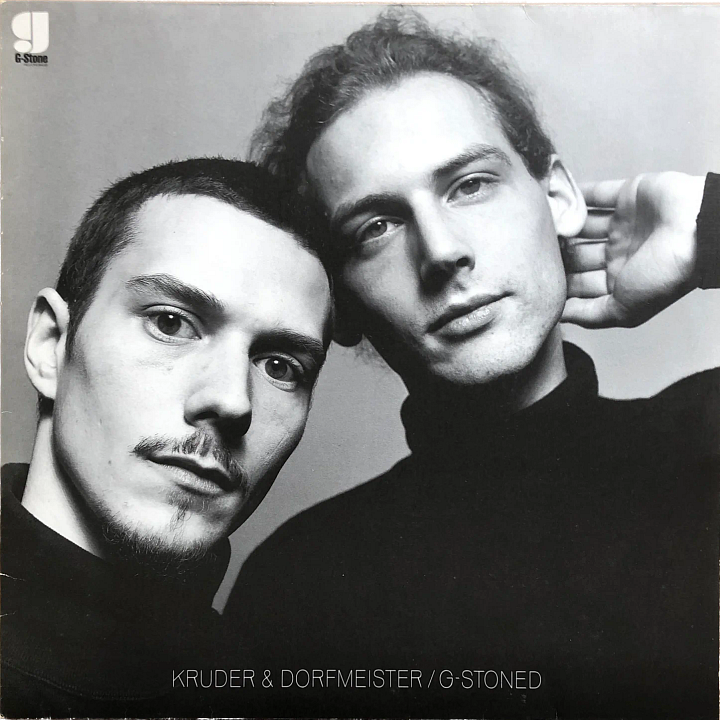

Out of these sessions emerged the G-Stoned EP, named after Vienna’s Grundsteingasse, where their home studio was located. The cover reconstructed Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends. Kruder always thought that his partner totally looked like a young Art Garfunkel.

They pressed up 1,000 units of the vinyl EP independently.

Two weeks later, they needed to repress.

It’s safe to say G-Stoned landed at exactly the right time.

In the UK, labels Mo’ Wax and Ninja Tune had started to release psychedelic hip-hop beats without vocals around ‘92.

That style would morph into trip-hop. Its defining albums by Massive Attack, Portishead and Tricky would be released in ‘94 and ‘95.

When G-Stoned came out in September ‘93, even acid jazz godfather Gilles Peterson supported K&D’s music in his influential BBC radio show.

In their hometown, people started showing up in unexpectedly large numbers to their DJ gigs, which contributed to K&D’s word-of-mouth fame.

They had to repress their debut EP every few weeks.

Off the back of that success, they flew over to London to connect and land remix jobs. They didn’t even have a manager, they just called the labels from payphones in the street. Everyone agreed to meet them.

Between 1993 and 1998, they created around 40 remixes for everyone from Madonna to Depeche Mode.

Still, they rejected most requests, famously turning down David Bowie, Sade, Elvis Costello and Grace Jones, because they didn’t like the songs they were asked to remix.

Back in those days, handing out sizeable remix cheques to in-demand underground producers was still considered a viable marketing strategy for the majors and even the bigger independent labels. Labels also used those remix assignments to get producers to sign contracts.

K&D never signed to a label, but happily snatched their remix budgets.

Along with their slick vintage style, their outsider attitude gave them an air of non-confirmist cool. Whether willing or not, they became the posterboys of the Vienna indie music scene.

They hadn’t even released an album yet.

DJ-Kicks: Kruder & Dorfmeister (1996)

In the early 1990s, Horst Weidenmüller, founder of the Berlin-based !K7 label, had an unusual idea: He wanted to commission DJ mixes for commercial distribution among music fans.

Back then, mixtapes were recorded live in the club or from the radio – and sold on the street. Some DJs pressed small runs of CDs to pass them around like business cards.

As rave culture entered the mainstream, Weidenmüller recognized a market gap.

His techno-focused X-Mix series started in ‘92. The successor DJ-Kicks kicked off in ‘95, with the first three issues again mixed by renowned techno DJs – CJ Bolland, Carl Craig and Claude Young.

Craig’s issue was considered a success, selling 15,000 copies.

Weidenmüller wanted K&D for the next issue of DJ-Kicks. But K&D didn’t play techno. They played downtempo and drum’n’bass, and they wanted to showcase new tracks from friends in London, Munich and Vienna, as well as some of the music they played out in the clubs. The tunes varied in tempo, sound and style so much that they wondered how to turn them into a coherent mix.

“Dub saved us”, Dorfmeister said in an interview with German weekly Der Spiegel at the time, referring to their use of studio effects adapted from Jamaican engineers. Instead of trying to beatmatch all songs, they simply shrouded them in atmospheric delay and reverb. That strategy enabled them to transition from hip-hop to drum’n’bass to dubby house to a Latin-tinged strain of electronic music that would be branded ‘future jazz’.

DJ-Kicks: Kruder & Dorfmeister, released in August ‘96, definitely hit the zeitgeist. It would go on to sell over 400,000 units.

The K&D Sessions (1998)

Around a year later, K&D gave a rare interview to a German journalist who just couldn’t grasp their level of fame. After all, they had “only released four original songs.” He was referring to the G-Stoned EP.

K&D felt offended. They considered their remixes original songs, and they had produced 40 of those over the past four years. For each one, they’d created a completely new beat and arrangement.

Still, those remixes were scattered over 12-inches and compilations; you had to be a record digger or a clubgoer to come across those tracks.

Hence the idea: another compilation for !K7. Once again, K&D would construct it in the style of a DJ mix and a dub session. Because of the size of their remix discography, it had to be a double disc. Each of the two CDs would have their own, distinct vibe – you’d play disc one before you went out, and disc two when you came back home.

The cover was shot by K&D’s friend, the designer Oliver Kartak, on a Lomo camera. The plan was for Kartak to document the actual cover shoot – but in the end, K&D liked his raw, analog photos much better.

The K&D Sessions would fly off the shelves.

It created such a massive hype that labels started signing Viennese producers left and right. The “coffee-house scene” became a subject of over-excited feature articles.

Neither K&D were fond of that label, nor were the other Vienna-based artists and labels.

For a retrospective oral history article in German electronic music magazine Groove, the late Mego founder Peter Rehberg provided his view:

“I was reading articles about the Vienna scene and thought: ‘Wait a moment, we have nothing to do with Kruder & Dorfmeister.’ […] They made lifestyle music for airport lounges. […] Of course we knew them, and they were really nice guys, but we had no musical connection to them.”

Sure, Rehberg’s reluctance is understandable. You can’t compare K&D’s pleasant chill-out beats to Mego’s more sophisticated, explorative catalogue. I’d argue there’s room for both though.

Regardless of such sentiment, the K&D success gave Vienna the reputation of an underground music hub that undoubtedly helped a lot of Austrian musicians and labels.

Naturally, that hype would cool down after a while. By the mid-2000s, downbeat had become a cussword.

20 years later, I think the music is ripe for reappraisal – with barber beats regularly dominating the Bandcamp charts and a new generation rediscovering 1990s electronic music and ambient sounds.

There’s no cool like 1990s cool, notwithstanding the Billy bookshelves.

Epilogue

For Peter Kruder and Richard Dorfmeister, The K&D Sessions marked the end of their recording career as a duo. Both would keep producing music under various solo monikers and in other groups though.

As Kruder & Dorfmeister, they would continue to play live gigs and DJ sets all around the world over the next decades.

More than 20 years after their last mutual release, they dusted off some old DATs containing beats made for their lost debut album, and finally released them in 2020, aptly calling that archival collection 1995.

For both releases, you will find other figures – sometimes higher, sometimes lower – but these numbers were provided to me directly by !K7 in 2024.

Great article! I do love K&D Sessions cd! As another reader, I listened it for the first time when I was a young adult and my musical taste was forming, so it had a huge impact. Another album that had an impact was Jazzanova's "The remixes 1997-2000".

Great article, thank you. I have a soft spot for K+D and this era of music as it was just kicking off at the beginning of my teenage musical appreciation. I agree that these guys were perhaps unfairly maligned during the 2000s; trip-hop becoming seen as slightly polite background music for dinner parties and adverts.

Maybe because it wasn't on K+D sessions and so it was less overplayed for me, but I really like their remix of Madonna 'Nothing Really Matters'