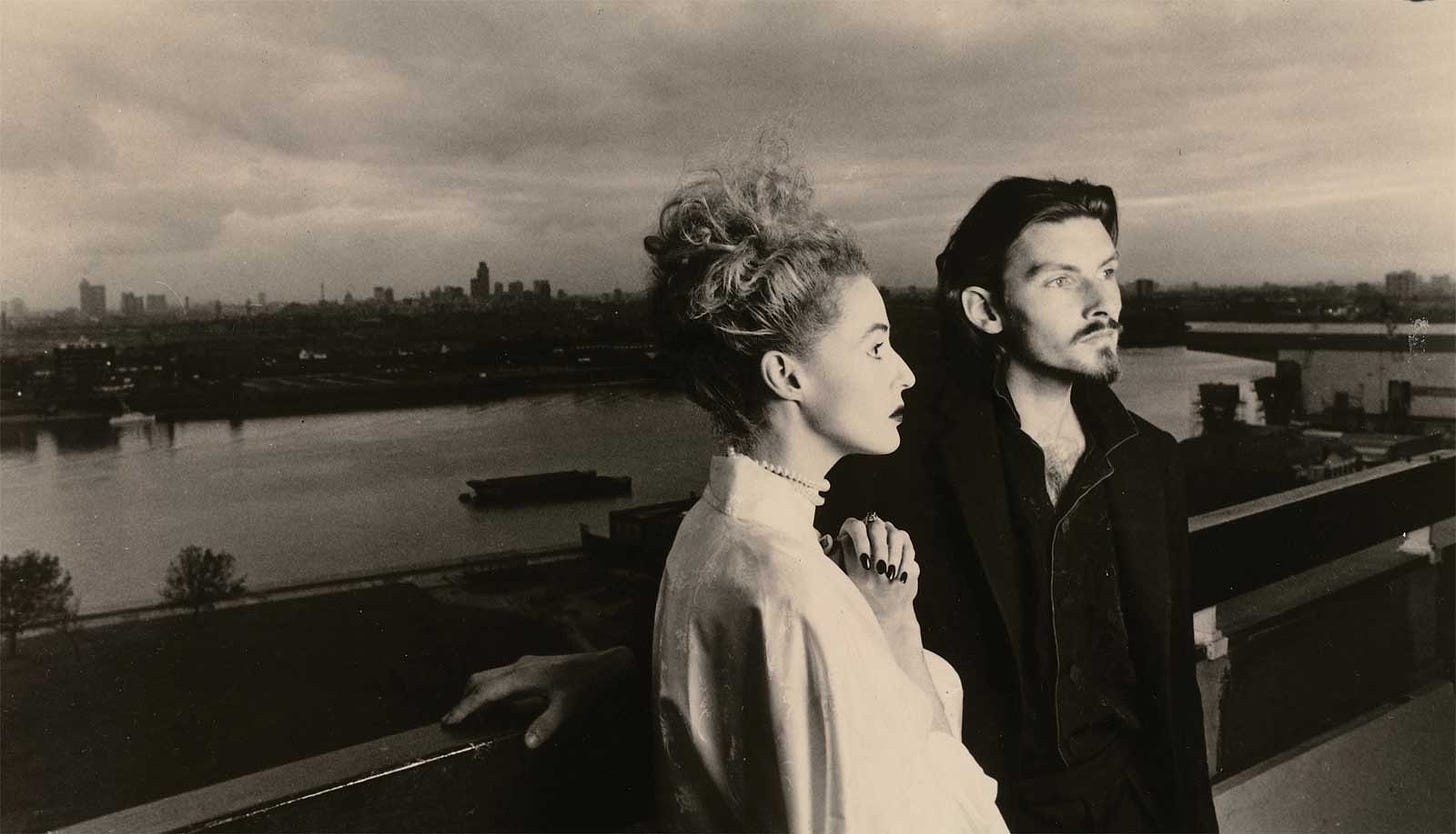

The Haunting Nostalgia of Dead Can Dance

A journey through the Australian duo's magical discography of 40 years

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to zensounds with Stephan Kunze to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.