Vapor Talks #10: Pizza Hotline

Videogame music producer Harvey Jones on his journey from dub techno to vaporwave and low poly drum'n'bass

Since his 2022 album Level Select went viral on YouTube, London-based producer Harvey Jones alias Pizza Hotline has been regularly topping the vaporwave charts on Bandcamp.

Harvey is spearheading a new subgenre dubbed ‘vaporbreaks’, a fresh look at the atmospheric drum’n’bass found in videogame soundtracks from the PlayStation 1&2 era (the late 1990s and early 2000s) through a nostalgic lens.

The 31-year old Welshman originally started making dub techno under the alias El Choop in the 2010s. When launching his artist moniker Pizza Hotline, he was inspired by classic vaporwave; during the pandemic he pivoted to a reimagining of classic videogame jungle as pioneered by Japanese producers like Soichi Terada.

In 2025, the prolific Mr. Jones released a sequel to his viral success, Dream Select, plus the brilliant Daydream Cast mix, a dedication to the ambient side of classic videogame soundtracks, and EPs with fellow producers Shirobon and Mitch Murder. For 2026, he already has a couple of interesting new releases in the works, among them an EP featuring a remix from a head honcho of the new UK jungle scene.

I spoke to Jones about videogame music production, his relationship to the vaporwave scene and which other talented producers in the vaporbreaks movement need to be watched closely right now.

I was happy that you agreed to do this interview, but unsure whether to include it in the Vapor Talks series. Do you actually see yourself as part of the vaporwave scene?

It’s an interesting question. I got into vaporwave around 2015 as a student in Bristol. Back then I was making dub techno under my other alias El Choop. My music was very dark and a bit more boring. [laughs] I was fascinated with vaporwave, because I found it very refreshing and playful. When I started Pizza Hotline, my first couple of releases were classic vaporwave, so I do consider myself within that sphere. Not so much the music I make today – however, the themes that are explored with it are indicative of vaporwave culture as well.

What kind of music were you into in your teenage years?

My dad was a guitarist, Stevie Ray Vaughan style, so I was surrounded by it but didn’t care or even like it until I was about 14, which is when I got a guitar and started listening to some blues and rock. I particularly loved the Stone Roses – there’s a blurriness in their music that has the quality of vaporwave in it, which you get in some of Jimi Hendrix’ stuff too.

One day a friend of mine was selling his DJ turntables, so I went and bought them, and that was the end. I became obsessed with electronic music. My friend handed me a cracked copy of Reason, so I put the guitar down and started making music with a computer. There were no good YouTube tutorials back then, so I was just working it all out by myself. I was the kind of guy who doesn’t care about school, but I was so focused on electronic music and music technology.

When I first got into it, I was listening to exclusively drum’n’bass and jungle, because that matched my teenage energy. I’d been making a bit of jungle, and I always quite thought the jungle I made was good, but I never really shared it with anyone. One day, I just dropped it all and listened only to techno and house for five years. I was so fanatical, it was like an illness.

You mentioned living in Bristol at the time?

Yeah. I’m actually from a tiny village in Wales called Montgomery. After school I ran away to Australia for a year and then decided to go to Bristol to study. I did my degree and I was still making music, but my dub techno project [El Choop] never really took off in a big way. That scene is very small and limited. I moved to London, and I was working at [department store] Harrod’s, DJing on the weekends and making music, maybe getting paid 150 quid for a remix, if I was lucky, or 100 pounds for a gig in Manchester with no travel. It was just not enough. I was really struggling.

I wanted to get into the video games industry, did lots of sound design practice and applied for so many game audio jobs, but nothing came back from any of them. So I had to make a decision whether to pursue a more conventional career. It seemed impossible to pursue music with the stuff I was making, so I just gave up. I thought, I’m just going to get a job and keep making music for fun.

How did you get into the videogame jungle then?

I’d always been into games but in the pandemic, I got really into old retro games and repairing consoles. I’d go to car boot sales, buy old PlayStations and Xboxes, repair them and put them on eBay. At the same time, I became totally fascinated by 90s era drum’n’bass and jungle hidden in them, so I made this giant YouTube playlist of all these tunes from old games, and they all had like 150 views. I was like, “Wow, no one’s listening to this but it’s such cool music.” I called the playlist “Level Select”, and I would just listen to this exclusively for one or two years. I was just consumed by it.

What’s the difference between the videogame drum’n’bass from that era and the type that was played in the clubs?

If you think about the context of the late 90s, you had artists making drum’n’bass music that was designed for clubs, and they were mixing it in actual studios on proper speakers. They had a good understanding of electronic music, so they would make good, chunky, rich-sounding music. Now think about a videogame developer in the 90s who’s trying to create games for 25- to 35-year old people who have disposable income and go to nightclubs. That was who the PlayStation was aimed at, so they’re trying to make their music sound edgy and cool and interesting. The developers would ask people who didn’t usually make that music, these regular game music composers who were used to making stuff for the NES, the SNES and the Sega Mega Drive.

I’ve spoken to some of these guys – some of them were computer programmers that made music [on the side], they weren’t necessarily artists. One of them told me they sat him in a room with a stack of [The] Prodigy CDs and said, “Just make it sound like this.” These people were approaching club music from a very different direction, and as a result, you’ve got music that’s not super underground-sounding but quite melodic and catchy. The mixdowns aren’t usually that good – the tracks don’t sound bassy, sometimes they even sound a bit bad, but I quite like that, because it’s innocent and a testament to how at the time they were trailblazing.

Enter someone like Soichi Terada, who was making house music in the 90s, and then made Sumo Jungle [1996]. The guy who was the Head of the studio making Ape Escape listened to that album and was like, “I want this music in the game.” I think Terada was originally trying to make Chicago house, but in his kind of own flavor, and then from that, he was making jungle, but this was very different, like Japanese jungle. Ape Escape [1999] really established that videogame jungle sound.

That makes sense. As someone who loved jungle and drum’n’bass in the mid- to late 1990s, I could sense the difference, but it was hard to pinpoint exactly.

Yeah, it’s a bit like vaporwave. It’s just about the way the music feels. Vaporwave is very centered around nostalgia, so that’s similar. Some people call my music vaporbreaks, which hasn’t really caught on. Back when I released Level Select, I started using this term ‘low poly drum’n’bass’, which is just a way to say that it sounds like low poly graphics. Some people say PS1 drum’n’bass, or PS1 jungle. I don’t really mind what people call my music though.

But the vaporwave influence is still there. How and when did you initially discover the music?

I remember exactly – I was in the live room of a recording studio at my university in Bristol, we were doing recordings, and my friend starts playing this music from his laptop. He’s like, “Guys, have you heard about this new sound?” I looked at his iTunes, and it was all Japanese writing with a picture of a Japanese woman on the beach. I was like, “What the fuck is that?” He said, “It’s called vaporwave. It’s made out of slowed down 80s music.” My first thought was, “What a load of shit.”

A few months later, I became so obsessed with it. I listened to vaporwave constantly for a year. I was following all the labels and bought all the vinyl. My mate would come round, we both thought it was so much fun because it was so easy to make. We were very technical, and my housemate was an electrical engineer, so we got this tape deck, took it apart and put a speed control in. We drilled a hole in and glued a knob on. We called it the vapor deck.

We used to get really wasted, smoke weed, laughing our heads off. We’d slow down everything – Queen, jungle, all this stuff. We’d record stuff from YouTube, and then vaporize it. We’d be up all night just laughing. That’s when we started Pizza Hotline. It was going to be me and this friend, but we didn’t really do anything with it.

About a year later, I was making some of my own vaporwave tunes, and I thought I’ll just put them out under the name Pizza Hotline, because it’s funny. That’s when I released my first EP deals with a western oil conglomerate (2018). It’s made from vinyl records and some field recordings I made in Bangkok. I released a couple more vaporwave albums, they’re still on my Bandcamp.

Then you switched it up with your videogame jungle style. Did you actually expect the impact that Level Select would have?

Absolutely not. I was just listening to all this music from videogames, and I was trying to recreate this sound that I couldn’t quite understand, very casually, not with any intent. I made this album, shared it to a few friends and almost didn’t release it because I wasn’t sure where to put it out.

There was this label called City Man Productions. They’re closed now, but I’d released a couple of vaporwave albums with them, so I didn’t think they would like this, but I sent it to them and asked, “Do you know any labels who’d want to release this?” They listened to it and were like, “We love it, let’s put it out.” And I thought, “Why would you want this on a vaporwave label?” Little did I know it kind of had the same feeling. I didn’t realize that at first, ironically.

It came out, went really well on Bandcamp, and then I submitted it to a YouTube channel called 4AM Breaks. They’ve been inactive recently, but they were a hugely influential channel for this kind of reimagining of drum’n’bass. They have 70,000 subscribers, and my video has 1.6 million views. I couldn’t believe that the people felt the same way I did about about it. I thought I was just in my own world listening to this old videogame music.

You’ve definitely kicked off a trend.

I know! Back then, when you typed ‘video game jungle’ or ‘PlayStation jungle’ into YouTube, you’d only get the old stuff. These days, you’ll find hundreds of mixes…

…most of them AI-generated…

…yeah, it’s awful. These channels have copied what I do, but it’s this horrible 100% AI-generated music. It’s just a huge pile of rubbish.

You said you’d wanted to work in videogames, but couldn’t get in. What happened after Level Select came out?

The hotline was ringing. [laughs] I’d actually given up on getting into [the games industry], but now that’s what I do really. I make music for games, but I’m also a full-time artist. One of the most notable calls I got was from Nike. They were working on a feature within Fortnite, so I made some music for that, which went really well. Another thing I made is the soundtrack to this game Motorslice. It isn’t actually out yet, but the demo is out, and it’s gotten huge attention online. It’s a really cool game, a bit like Prince of Persia, so it’s like Parkour, free running, but in the future, and the graphics have this pixelated PS1 look. I’m really pleased with how the music came out. That’ll be coming out as an album in its own right.

Dream Select, the 2025 sequel to Level Select, was one of the year’s most popular albums in Bandcamp’s vaporwave section. The artwork is really strong too, a mix of Y2K videogame and Frutiger Aero vibes.

Yeah, I worked with a guy called Equip Studio. He messaged me, as he was just starting his own studio for interactive media and videogame branding. He’s a fan of my music, so he offered to do some work for free. He did my logo too, and he did such an amazing job. All I had in my head was the original Xbox One menu screen. It’s black and green and has this interesting alien Y2K vibe. He combined it with the PS2 clock and created this cool object. There are little easter eggs in the artwork – my postcode is on there, but backwards. There’s a little message to my wife, which I try to do on every release, so it says Mrs. Hotline with a little heart. Actually, there’s a track on the album called “Mrs. Hotline” because she’d come into my studio while I made it and be like, “This one’s really good!”

A bunch of other producers have started making vaporbreaks over the last three years as well, right?

Yeah, I get a lot of messages from my Discord community, and all the producers gather in there, which is cool. There’s a guy called Dusqk – he’s really good. His stuff’s probably the best-produced music I’ve heard in the scene. I rarely hear something that blows my mind in terms of the production, but Dusqk was one of them. When I heard that, I had to message him immediately.

He’s brilliant. Sanctuary OS has been on rotation here for months.

It’s fantastic. Who else is there?

I like MICROMECHA. He started out doing barber beats but pivoted to videogame jungle. Which producers do you rate?

This guy called KADE, his stuff’s fantastic. He doesn’t get much attention. Another one is YET soundsystem, his music’s really good as well. And arcologies from Chicago. These are more like hidden gems though.

Is there a connection between vaporbreaks and the new UK jungle scene, like Tim Reaper, Sherelle and those people?

I know Tim Reaper. He came on my radio show. I just messaged him, and he replied he likes my music, so there is a connection with him. I’ve actually got an EP coming out soon with a Tim Reaper remix on it. I’m starting this new series called Demo Disc. They’re vinyl records, but I’ve stolen the graphics from the PS1 demo discs, so there’s a little CD in the center. They’re going to be these almost traditional dance releases where it’s two originals and two remixes.

But [Reaper]’s the only one who I’m connected with. I haven’t really contacted anyone else in the traditional UK scene. I honestly have so much on my plate that I’m just staying quiet at the moment. Also I don’t really play much in London, while I’ve actually played Flamingofest, that huge vaporwave festival in America, twice. 80% of my streams are coming from America, so many of my fans are over there.

What else are you working on right now?

I’m always working on four or five albums on the go for one or two years. I’ll make a track, and I’ll be like, “Oh, that’ll fit in there”, and I’ll drop it into the little bucket that’s labeled Frutiger Aero. I’ll make three tracks in one style, and then I’ll stop working on them. Three or fours months later, I’ll come back to them and add another track or two, and at some point I’ll finish the whole thing in one intensive week. I don’t know if that’s a product of ADHD, but that’s just seems to be the way I work on things.

I’m currently making an album which is my own interpretation of that Frutiger Aero, post-vaporwave thing, this super clean, minimal, optimistic elevator music. Another one I’m working on is a jungle album about car culture. It’s about this pizza delivery guy who also goes drifting and nighttime racing. This is my genius idea, man. It’s gonna make me millions. [laughs]

Listen to Pizza Hotline on Bandcamp

Pizza Hotline’s Top 10 Vaporwave Albums

(unranked)

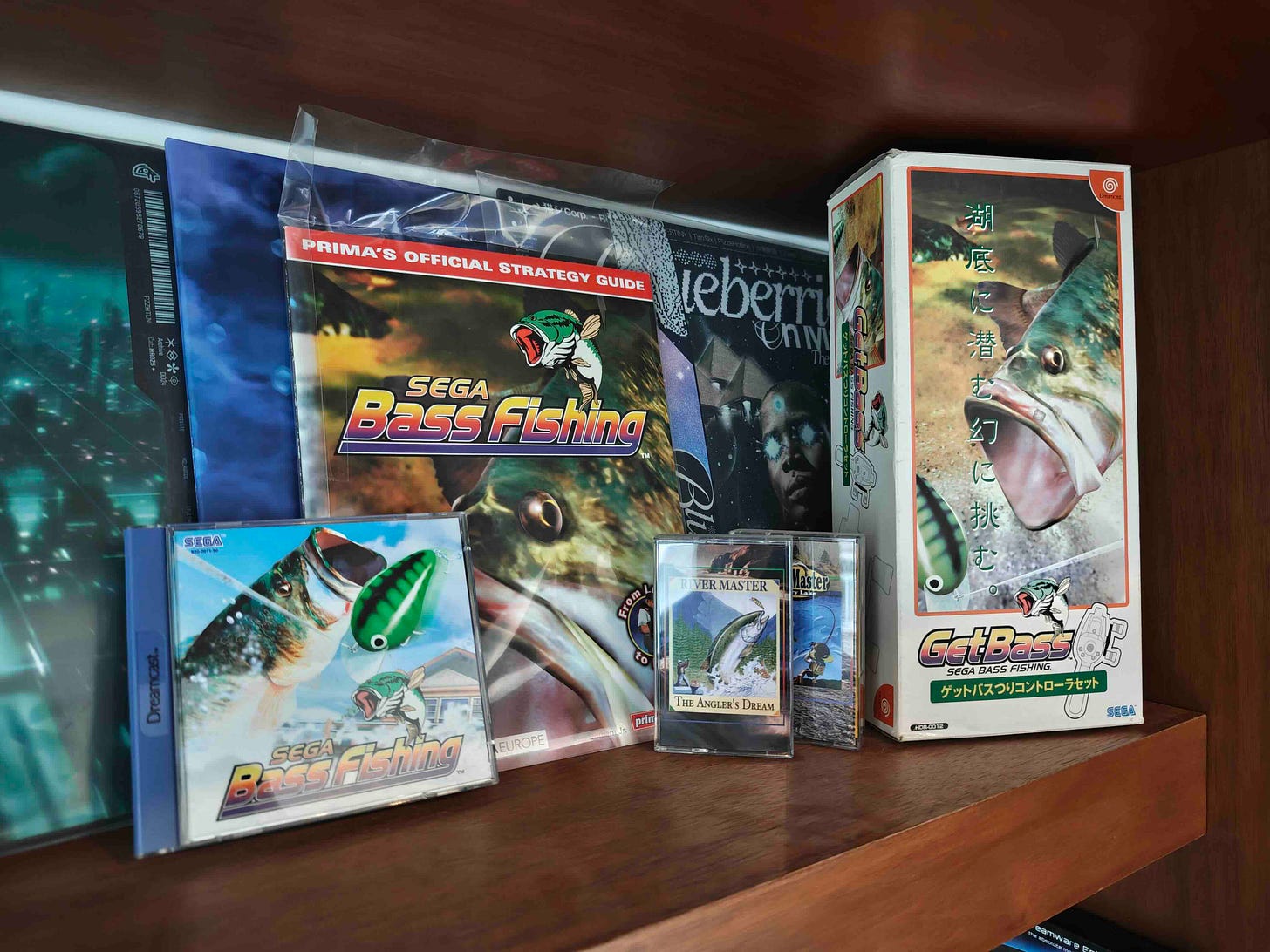

River Master – The Angler’s Dream (self-released, 2022)

River Master – Memory Lake (self-released, 2023)

HONG KONG EXPRESS – 浪漫的夢想 [’ROMANTIC DREAM’] (Eternal Fortune, 2019)

Webinar™ – w w w . d e e p d i v e . c o m (Whitespace, 2021)

Infinity Frequencies – Computer Death (self-released, 2013)

Professor Creepshow – 32 Bit Breaks Vol. 1 (Planet SIC, 2020)

カイヤン〜 – 水中ユニコード˚ (Tetra Systems, 2016)

s a k i 夢 – 夢の中で失われました (self-released, 2016)

Farragol – It’s cold outside, but I’m hot (self-released, 2022)

いすゞ・ピアッツァ ENTERPRISES– ISUZU PIAZZA (self-released, 2016)